What Will Happen if Overfishing Continues

Each year, elementary schools around the United States put on plays meant to celebrate and recreate the magic of the first Thanksgiving. At some point in your education, you too may have donned a construction paper pilgrim hat or a colorful collection of turkey feathers while acting out what supposedly happened during that fateful post-harvest feast.

Even if you weren't involved in a kindergarten stage production, many of us were taught the classic tale of the first Thanksgiving: that a group of friendly Native Americans welcomed the pilgrims to the new world over a meal of turkey and potatoes after a successful harvest. But as many of us approached adulthood — and possibly learned more about how, throughout history, the U.S. engaged in the systematic displacement and genocide of Indigenous populations across the country — the sneaking suspicion that there may have been more to the story of Thanksgiving only grew stronger.

And for good reason. The first Thanksgiving wasn't at all the story that's been mythologized and rewritten for history books. While there may be some small segments of truth embedded in the narrative we're told, it's not a coincidence that many Native American groups regard this holiday as a time of mourning. To shed light on a more historically accurate version of events, we're taking a look at what really took place during the first Thanksgiving.

The Pilgrims Had a Difficult Start After Landing

The supposed story of the pilgrims begins in 1620 when a band of 102 travelers set sail from England on the Mayflower. They were mainly looking for economic opportunities and the chance to own land after living in poverty for years. Their voyage across the Atlantic lasted for a grueling 66 days before they landed in early November, not at Plymouth Rock, but near the tip of Cape Cod in what's known today as Provincetown.

Soon after, pilgrims encountered members of the Wampanoag Nation after venturing back and forth from the ship to the land. From this point in the story, the unflattering truth begins to unravel. As Wampanoag activist Wamsutta Frank James explains, "The pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans" — the colonists robbed the tribe of food and other goods they had stored up to use throughout the winter.

The incident left the group justifiably upset, and they fired arrows to let the pilgrims know it was time to move on. The pilgrims sailed down to Plymouth Rock, where most of them spent their first brutal winter onboard the cramped ship. Only half the passengers lived to see spring; many died of exposure and disease while the boat remained anchored in Massachusetts Bay. It was around March of 1621 when they finally ventured ashore.

One major myth that commonly comes into play with the Thanksgiving story was that the Native Americans at Plymouth had never seen Europeans before. In fact, the members of the Abenaki tribe, who greeted the pilgrims after they came ashore, actually did so in English. They were joined by Squanto of the Patuxet tribe, who had formerly been kidnapped and enslaved in London by an English sea captain before escaping back to America.

Squanto interpreted for the colonists, helping them arrange an alliance with the local Wampanoag Chief, Massasoit, and brokering deals in which the pilgrims gave the Wampanoag weapons in exchange for food. With help from their new allies, the colonists enjoyed their first successful crop harvest in late summer of 1621.

According to a document written by pilgrim Edward Winslow, the colonists did invite Chief Massasoit and some members of his tribe to a great feast that lasted three days. In Winslow's description, however, there was no mention of turkey or potatoes (which had barely just made their way to North America in the early 1600s). It seems the first Thanksgiving feast consisted of fowl and deer; having run out of sugar, the pilgrims were also unable to prepare baked items.

Still, many historians believe this event was far from the first Thanksgiving in North America. As early as 1565, Spanish settlers feasted with local Native American tribes in Florida, while yet another similar feast was held in Virginia in 1619. Others argue that the pilgrims would have considered their first true Thanksgiving to have been a day of celebration declared by governor John Winthrop in 1637. The event was meant to honor a group of colonists who joined Narragansett and Mohegan tribal allies in murdering over 500 people from the Pequot tribe in what is now Connecticut.

The Plymouth Rock Feast Wasn't the End of the Story

What we know today as the first Thanksgiving may have represented a high point in relations between the pilgrims and Wampanoag tribal groups, who proved to be invaluable allies. But the story doesn't end there. Throughout the 17th century, what began as a small group of colonists multiplied by the thousands.

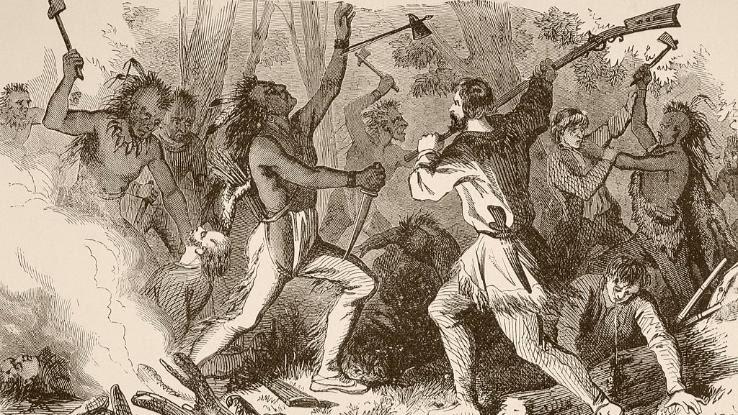

The colonists embarked on violent quests to seize land from Indigenous groups, and they also brought with them diseases that devastated local populations. Tensions between tribal groups and pilgrims continued to build during the 50 years following the "first Thanksgiving," culminating in the outbreak of King Philip's War in 1675. English colonists massacred former allies of the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes and assassinated tribal leaders, ultimately ending the significant presence of Native American groups in the region and leading to further colonial expansion.

As time went on, the violent ending to the initially stable relations between pilgrims and tribal groups was gradually forgotten by history. Its association with Thanksgiving is a relatively recent development — as is the holiday as we know it today. It wasn't until 1863 that President Abraham Lincoln declared it an annual holiday in America. While the fictitious notions of the first Thanksgiving may seem pleasant to many Americans, they weigh heavily on Indigenous populations. Each year, they're confronted with enduring misrepresentations of their cultural histories, and for decades their generational trauma, perpetuated in part by Thanksgiving myths, has remained largely unaddressed.

Rethinking Our Notions of Thanksgiving Today

Many people living in the U.S. tend to associate the first Thanksgiving with the birth of the country itself. And this means they forget — or were unaware — that the habitation history of this land began when the first Indigenous people arrived on the North American continent more than 15,000 years ago.

While our traditional retelling of the first Thanksgiving is riddled with historical inaccuracies, there's a basic certainty to remember: If not for the generosity of the Native Americans at Plymouth Rock, the pilgrims likely wouldn't have survived. It's time to consider how, on multiple levels, we should be showing gratitude and respect towards Indigenous communities — and that starts with telling the truth. "It's past time to honor the Indigenous resistance, tell our story as it really happened, and undo romanticized notions of the holiday that have long suppressed our perspective," says Christine Nobiss, Indigenous activist and Decolonizer with Seed Sovereignty.

The sentiments behind our observance of Thanksgiving — like togetherness, family and appreciation — are worth celebrating. But it's vital to understand that, for many Native American groups, the holiday isn't something positive. Instead, it's "a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands, and the relentless assault on Native culture" that have occurred since European colonists first set foot on this land.

But it's also an opportunity to honor Indigenous groups by uplifting their voices and combating the ongoing erasure of Native American history that Thanksgiving myths have prolonged. This Thanksgiving, you can get started in these efforts by reading more about the Truthsgiving movement; you'll discover different ways you can elevate Indigenous populations this November and all year long. From learning about the group whose lands you're living on and reading works by Indigenous authors to hearing the history of Thanksgiving from Native American perspectives and supporting Indigenous-led political initiatives, you can help affirm community experiences and raise awareness about fundamental truths. And that's really something worth celebrating.

Source: https://www.reference.com/history/what-happened-first-thanksgiving?utm_content=params%3Ao%3D740005%26ad%3DdirN%26qo%3DserpIndex&ueid=a777bfd8-4b31-4df4-bc14-67d2f617c5ff

0 Response to "What Will Happen if Overfishing Continues"

Mag-post ng isang Komento